|

A huge theme for this coming year is this idea of embodiment and how we can live our lives in ways that honor our bodies and their physical and emotional needs. As the year comes to an end, here are a few questions we can reflect on, to help us set the stage for living more embodied lives in 2022:

The answers to these questions will vary from day to day and from moment to moment, and there is no wrong answer. What’s true for you right now? Whether the experience of being in your body is a very pleasant one in this moment (maybe you are enjoying a delicious meal, or smelling a scented candle or you just finished a really fulfilling movement session) or a very unpleasant one (maybe you are sick or injured and in a lot of physical pain, maybe you are suffering from depression or another type of emotional pain), making the time to simply take note of how you feel can be so helpful and important.

Again, there is no blanket right or wrong answer here, but these questions can help you explore the right answers for you. If there is a form of movement that your body is craving, how can you make that into a regular practice? If there is a type of food that makes you feel good from the inside out, how can you integrate that into your diet? What are the activities that make you happy, that make your heart sing? How can you carve out more time to do them more regularly? Is there anything that doesn’t make you feel good, that you can do away with in your life, or make less time for? Have you been getting enough rest on a weekly basis, or does something need to change so that you can get the rest you need? We have a lot more control over the experiences within our bodies than we think. But rarely are we taught to tune into the body, to learn and understand its language, to listen and to give it what it needs. More often than not, we are taught that our bodies are dirty, we are taught to feel guilty for seeking pleasure, we are taught to neglect our body’s needs and to treat it like a machine that can be pushed around to yield the same level (if not ever-increasing levels) of output and productivity every day no matter what. In fact, most of us treat our bodies even worse than machines, because even machines need maintenance from time to time... yet how many of us take the time to give our bodies the maintenance they need? Now, if thinking about these questions brings up anxiety, resistance, or resentment for you, notice that too. Again, there is no wrong answer. What’s coming up for you? How do these questions make you feel, and why? No matter what is coming up for you, your feelings are valid and deserving of further exploration. I am wishing you a fruitful time of reflection as the year comes to an end. May you make new discoveries that will help you step into a better, happier, and more embodied phase of your life! Was This Post Helpful?Did you find this post helpful? Would you like to see more like it? If so, comment below letting us know!

You can also visit our blog map to find more of our articles, or subscribe to our newsletter or Facebook page to be the first to find out about our next post. And you'd like to learn belly dance online, check out our available classes here.

2 Comments

Not sure what to wear to your first belly dance class? You're not alone! This is one of the most common questions I get from brand new belly dance students, so I decided to make a video and blog post to address it. There is a misconception that you have to show your belly or wear a fancy costume just to go to class... but this is simply not the case. In reality, what you need to wear is anything that makes you happy, that you feel comfortable and confident in, and that allows you to move freely. You don't have to show your belly unless that makes you happy and you are comfortable with it. It does help to wear clothes that aren't too loose just so your teacher can see your movements, but you don't have to show skin or wear anything super tight if you are not comfortable with that. It's also nice to bring a hip scarf or any fabric to tie around your hips to emphasize your movements, but that is not required. As for footwear, typically we dance barefoot, but if you are uncomfortable dancing on bare feet, you can wear dance slippers, jazz shoes or foot undeez instead. If you normally wear orthotics, it's acceptable for you to wear whatever shoes and orthotic inserts you normally wear, but you'll need to check with your teacher about their policy for wearing "street shoes" inside the studio. It's possible that they might ask you to have designated shoes just for dancing if street shoes are not allowed on the studio floors. And that's it, so plain and simple! Wear anything comfortable that allows you to move and allows for your movements to be seen, and have fun! Was This Post Helpful?Did you find this post helpful? Would you like to see more like it? If so, comment below letting us know!

You can also visit our blog map to find more of our articles, or subscribe to our newsletter or Facebook page to be the first to find out about our next post. And you'd like to learn belly dance online, check out our available classes here. If you're feeling this current of heavy, overwhelming, or exhausting energy right now, you are not alone! It's normal to get burned out in the summer, but this moment in time feels extra exhausting. We are still living through a time of fear, uncertainty, major shifts and transitions... I just want you to know that regardless of how difficult things are right now, you're doing an amazing job. The challenges you've overcome these past 2 years were no small feats, and you're still here, you're still standing. There's so much to be said about that! So acknowledge your victories and take it one step at a time when it all feels like it's too much. Slow down or pause when you need to, and be kind to yourself through it all... no matter what. What are some tools in your figurative toolbox that help you get through tough times? For me dance, yoga, other forms of movement, breathwork, music and writing are great ways to regulate my nervous system so I'm not constantly being swept up by the storms of life. Make sure to have at least a few of your own "tools" at your disposal and to use at least one of them each day (whichever one feels the most approachable or pleasant in those difficult moments, especially when inner resistance hits). Take care of yourself first and foremost and help whomever you can along the way. Despite all the terrible things that are happening, I also see support systems strengthening, and communities that will help build a better future forming and growing. You are loved and supported... even when it doesn't feel like it. You can do this! Need some extra help? Try out these simple breathing exercises taught by Namita of Yoganama: Was This Post Helpful? Did you find this post helpful? Would you like to see more like it? If so, comment below letting us know!

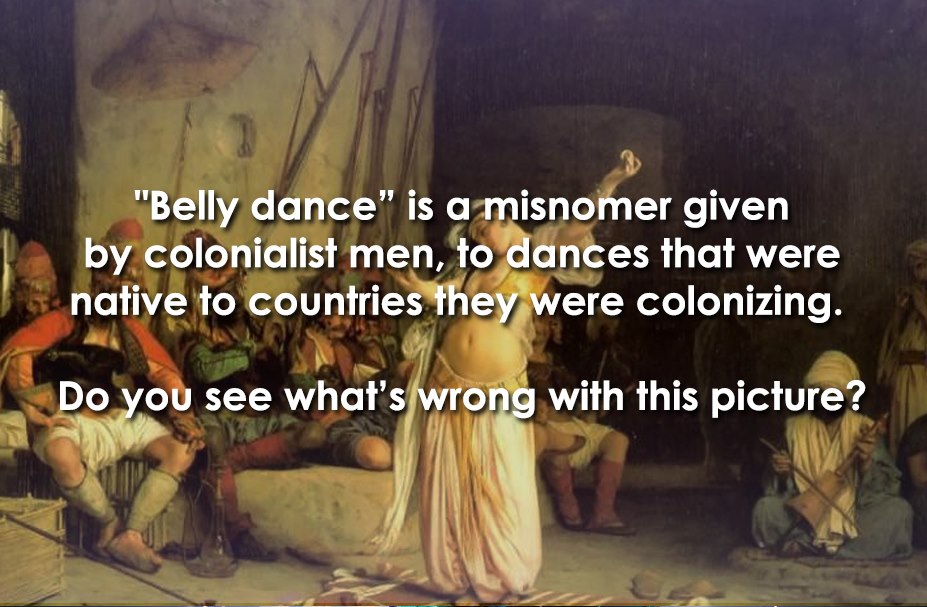

You can also visit our blog map to find more articles, or subscribe to our newsletter or Facebook page to be the first to find out about our next post. If you'd like to learn belly dance online with us, check out our available classes here. “Belly dance” is a colonial misnomer placed on dances from the Middle East, North Africa, Turkey and Greece. It stereotypes and pigeonholes a rich and complex art form and erases the people and cultures it comes from. Why are we still using the term? Let’s unpack a bit of the history and cultural baggage behind it. Over the past few years and especially the past couple of months, I have been doing a lot of deep reflection on the art form I have dedicated the latter half of my life to, the dance most people where I'm from know as "belly dance." I have been reflecting deeply on the terminology I use, how to define this dance and how to describe what I do to people who don't know me, to paint a more accurate picture of my life's work. I have also been reflecting on my role as a non-Arab woman, living in the US and teaching an Arab dance. The truth is that average people in our culture don't actually know what belly dance is, and upon hearing this term the image they conjure up in their heads is, at worst, a wildly inaccurate representation of what I do, and at best it is a simplistic and incomplete view of an extremely rich, culturally diverse and socially complex art form that is both incredibly beautiful and powerfully transformative. The picture of me, sexily shaking my bits in a sparkly 2-piece costume does not even begin to account for everything this dance is, everything it represents, and everything that is involved when someone decides to seriously learn belly dance. The costume and the movement are only a tiny fraction of what this dance actually is or could be. Orientalist painting La danse de l’almée by Jean-Léon Gérôme "Belly dance" is a broad umbrella term for Middle Eastern, North African, Hellenic & Turkic (MENAHT) dances that involve articulated movements of the hips and torso. But belly dance is also a misnomer given by colonialist men, to dances that were native to countries they were colonizing, dances that in many cases were primarily done by women. Do you see what’s wrong with this picture? The term caught on, and these days it also encompasses the versions of these dances which have evolved in non-native countries all over the world, including fusion forms that bear less resemblance to the original dances that still live on and continue to evolve in MENAHT countries today. Because it’s such a convenient, broad term that encompasses such a variety of dances, it has been difficult to come up with any term to replace it. It’s also the only term that the general public knows them by, so it’s how new people interested in learning these dances are able to find their teachers. But it is also simultaneously a term that pigeonholes us into stereotypes and limiting roles, and it can also discourage people from learning this dance altogether. Why is that? First of all, “belly dance” is a term that zooms in on one specific body part. It leads some people to think that all it takes is to shake or undulate this body part, and thereby dismiss it as a silly activity that doesn’t warrant any serious study or dedication. At the same time, others might think they could never do it because their bodies just don’t move that way (spoiler alert: anyone’s body could move that way with enough practice and good teaching). Additionally, I would estimate that there are millions of women in our country who would give this dance a try if its name didn’t immediately confront them with a part of their body that is tied with their self-esteem in a negative way. In our culture, we are taught that “fat = BAD” and that we must have a toned belly to be deemed beautiful and worthy. This is a lie that many women are finally beginning to unpack and unlearn, but still for most women the idea of putting so much focus on a physical part of ourselves that we dislike can be extremely intimidating and off-putting. Yet the reality is that people of any body type can belly dance. It’s a dance that looks beautiful on any body, without weight, age, or gender restrictions. And it’s a dance that involves so much more than just belly, hips and chest movements. It also involves footwork, arm movements, feeling and expression, understanding various different genres of MENAHT music, instruments and rhythms, familiarity with classic Arabic songs, connecting with the lyrics in their original language/s, and knowing the basics of different folkloric dances from various regions of the Middle East. When we use the misnomer “belly dance,” we are omitting these important aspects of the art form and contributing towards the erasure of the rich and diverse cultures and people that it comes from. MENAHT people and their cultures are not well represented in here in the United States. They are stereotyped and misunderstood at best, profiled and oppressed at worst. To practice, perform and teach a dance that comes from their countries without acknowledging their cultural context contributes to the stereotyping and oppression so many still suffer from. So, what do we call it instead? Years into my personal reflections on this subject, I still have not arrived at a concrete answer. I am becoming comfortable with the idea that this is an evolving discussion and that my thoughts and approach towards this subject will continue to evolve and change over the years. I am comfortable with the fact that people’s opinions on this subject will differ and many disagree with my approach. I respect those differing opinions, and accept that everyone is arriving at their own answers in their own time. What’s most important is that we continue to learn and be open to having these conversations, and especially to hearing the opinions and experiences of dancers from source countries! While I still continue to use “belly dance” as a broad term, for lack of a better broad term, for simplicity’s sake and to help new students and clients find me, more and more I refer to what I perform and teach as “raqs sharqi” among my existing students and even to people outside of the belly dance industry/community. Calling it “belly dance” encourages assumptions and stereotypes they already held. “Raqs sharqi” piques their curiosity and invites discussion (with that said, when I am dancing fusion, or dancing to non-Arabic music, I revert back to the broad term “belly dance”). Raqs sharqi is Arabic for “Eastern dance” or “Oriental dance.” It’s what Egyptians call the stage version of the dance we know as “belly dance.” Since I primarily focus on learning from Egyptian style teachers, that can be a fitting term for me to use. But the term will depend on the language, so for a Turkish style dancer, perhaps “Oryantal dans” (the Turkish language equivalent of the term) could be more fitting. What’s important to note is that nowhere in MENAHT countries are any of the dances we call “belly dance” referred to by a body part like it is here, but since my studies focus on Egyptian style, I will be using Egyptian (Arabic) terminology on this post, and please be aware that my knowledge of the history of this dance is very much Egypt-centric. Raqs sharqi is a stage adaptation of various dances mixed together, including raqs baladi ("country dance"), one of the social dances done in Egypt which uses hip and chest "isolations", shimmies and basic steps and is very casual and relaxed ("belly dance" in its most raw, unpolished, original form). This type of social dance is not exclusive to Egypt, it's done in most if not all Arab countries (alongside other social dances), it’s done by women and men in many cases, but in some regions it may be done primarily by women. It is simply the way people dance amongst each other when they get together for a party, wedding or other celebration. The specific music used, the stylization of the movements and the name used to refer to this type of dancing will vary by country/region. There are non-Arab countries in the Middle East/Mediterranean that dance socially like that, in their own ways, like Israel, Turkey (where it's called çifteteli) and Greece (tsifteteli). In Egypt, the stage adaptation we call "raqs sharqi" ("oriental dance") came about in the late 1800’s and incorporated elements of raqs baladi (“country dance”) with the performative styles that were done by the ghawazee and awalim who were professional dancers/entertainers who performed at weddings and other celebrations at the time. It also incorporated some elements of non-MENAHT dances like ballet and ballroom and other forms that the earliest raqs sharqi dancers happened to have trained in (Latin dances, acrobatics, and more). The evolution of this dance is very interesting as all the most famous dancers had such a unique and different style and each became highly influential in shaping the development of the dance. Much of the evolution of raqs sharqi happened around the time of the Golden Era of Egyptian cinema, and people all over the Arabic-speaking world were watching Egyptian movies which often featured dancing scenes by famous raqs sharqi dancers, who were actresses too! Lastly, raqs sharqi also incorporates bits of various different Arab folk dances when the music calls for it… it’s a lot to learn! Here in the US, this very rich and complex dance was reduced to just a titillating dance for many reasons. Colonialism, orientalism, patriarchy to name a few. When “belly dance” was originally introduced to the “Western” world in the late 1800s, it was not raqs sharqi but social and folkloric dances from colonized countries (in North Africa and the Middle East), done by women who were brought over from those countries by colonizer men (French, British, Americans), taken completely out of their native context, and presented in a sensationalized way to make money for those men. This was happening during a time when Western women wore corsets and showing your ankles as a woman was considered scandalous. So even though those dancers brought over originally were fully covered when performing, the fact that they moved their hips freely was considered extremely vulgar and scandalous and it attracted viewers due to the shock factor. And so the infamous reputation of “belly dance” began and we have never been able to fully overcome those associations. The real evolution and growth in popularity of “belly dance” in the United States didn’t really start until around the 1950’s, 60’s, and 70’s though, as immigrant dancers from different countries in the Middle East (Turkey, Lebanon, Syria, Egypt, etc) began to set up classes here and taught Americans how to perform. The style that evolved here was called “American cabaret,” it evolved differently in different regions of the US and was a mix of various Middle Eastern styles of belly dance, since this country is such a melting pot of different cultures. In the 70’s, Middle Eastern clubs were booming, featuring long belly dance shows with live music, and the bands here were made up of musicians from all over the Middle East, so American dancers at the time had to know how to dance to Arabic, Turkish, and Greek music. But without the social/cultural context, and with the revealing costumes worn, what Americans saw was still a scandalous dance. And in the eyes of the patriarchy, there is no reason a woman would want to move her body like that other than to please or seduce a man. This, coupled with ignorant but prevalent Orientalist stereotypes of Arabs and Middle Easterners in general meant that the image of the “sultan’s harem” and the idea of “seducing the sultan” became intricately connected with the image of the “belly dancer” here in the US. Of course, since sex sells, this is something that many club owners and belly dancers themselves used to their advantage. This helped to cement the reputation of “belly dance” as something purely sexual and scandalous here in the US, which unfortunately led to it being reduced, dismissed, and ridiculed by the general public, something that continues to this day. Here it’s important to add that performing belly dance/raqs sharqi in public is also very taboo in most MENAHT countries. In some countries it is forbidden, in others it is forbidden for natives but allowed for foreigners, and in others it is allowed but you are ostracized for being a belly dancer. In Egypt for example, belly dance (raqs baladi & raqs sharqi) is a huge part of their culture, it’s done socially at every gathering and at any major celebration a belly dancer is hired to perform and is often the main attraction. They love and appreciate the dance, and they generally dance the social form of it at parties and other gatherings (where it happens in gender-segregated settings for the more religiously conservative/modest, and in mix-gender settings for the less conservative), but a woman who is paid to dance is not seen as respectable. So belly dance being considered “provocative” isn’t necessarily unique to our culture. It’s just that in the cultures of origin, there are layers of appreciation and admiration amid the layers of taboo and condemnation. In the countries of origin, it is done socially for fun and celebration and not just viewed as a dance of seduction and provocation. To really do this dance justice we have to get comfortable with this dichotomy instead of pigeonholing ourselves into a single stereotype. To do so as non-MENAHT outsiders means opening up a door into cultures and customs we may not otherwise have been exposed to. We have to learn movements that are difficult for us because we haven’t been doing them socially with our family and friends our whole lives, but which are so beneficial and rewarding for countless reasons… but this dance is so much more than just movement. Music, culture, and language are all intricately connected with the movements of this dance. It is a lifelong study, which far from just working your belly, will work your entire body, your brain, and your heart while deepening your connection to the rest of humanity. Was This Post Helpful?Was this post helpful? Would you like to learn more about belly dance/raqs sharqi? Hit "like" below, share, and leave a comment with your feedback!

You can also visit our blog map to find more posts like this, or subscribe to our newsletter or Facebook page to be the first to find out about our next post. If you'd like to learn belly dance online with us, check out our available classes here. I was thrilled to wake up this morning to a post from one of my dear students, linking to a spineuniverse.com article named Belly Dance Your Back Pain Away. Call me a pessimist, but I don't usually expect much from articles written about belly dance in the mainstream. They tend to be, at best, just fluff pieces that totally minimize what belly dance really is, or at worst they could be full of stereotypes and misinformation. This time around, I was pleasantly surprised. For once, an accurate and informative take on the dance form we love so much - and from a medical source, at that! So let's break down the many benefits of belly dance as listed on the article, and why I love them so much:

That just about covers the benefits mentioned in the article (if you haven't checked it out by now, you can read it here.) Belly dance offers countless other benefits as well, which you may have noticed if you already practice it. What positive impact has belly dance had in your life, health, or well-being? What are the benefits you've personally experienced from it? Was This Post Helpful?Was this post helpful? Would you like to learn more about belly dance? Hit "like" below, share, and leave a comment with your feedback!

You can also visit our blog map to find more posts like this, or subscribe to our newsletter, YouTube channel, or Facebook page to be the first to find out about our next post. If you'd like to learn belly dance online with us, check out our available classes here. What is mahraganat music & dance? Today our guest author Aasiyah explains the origin and cultural context of this musical genre that is taking the belly dance world by storm.  Recently there has been quite a bit of discussion in the belly dance world regarding mahraganat- the music, the dance associated with the music, its incorporation into belly dance performances, and costuming. Even though the music genre is incredibly popular, both in Egypt and abroad, there is still a good deal of confusion and misunderstanding of what is mahraganat. First, a vocabulary lesson: mahraganat (مهرجانات) translates to ‘festivals’, plural. Mahragan (مهرجان) translates to ‘festival’, singular. The style of music is named as such because of its origins. The music itself can be labeled as either mahraganat or mahragan; the words are used interchangeably. So, what are the origins of this music genre? I wrote and published an article in 2018 breaking down the history of mahraganat. Briefly, mahraganat is a type of music that originated from the lower socio-economic classes of Cairo. The genre began as an underground music movement when pioneering producers DJ Figo and Ala Fifty created loud, exciting music using predominantly synthesizers and autotune in the underground clubs of the Egyptian ghettos. 2012 concert featuring some of the original pioneers of Mahraganat: MC Amin, Saddat & Fifty From the Underground to the Vernacular The genre quickly moved from the underground clubs to sha3bi street weddings and into the broader Egyptian population when it became a soundtrack to the 2011 revolution. Mahraganat is a type of sha3bi music in the sense that it is a popular genre of music. However, just like sha3bi music is not pop music, mahraganat is not technically sha3bi music. The language/word choice, vocal usage, and composition are unique to mahragan. And even though mahraganat may sample some aspects of western hip hop and rap, it is neither of those things. Since the mid-2010s, the music genre has, for lack of a better term, blown up. Mahraganat is no longer reserved for underground parties or sha3bi weddings, or even for Egyptians as a matter of fact. The music is played in both high-end weddings, exclusive night clubs, cabarets, and tuk-tuks alike. The average Egyptian, the wealthy, the poor, the foreigner, all dance to this music. It is is played in clubs and restaurants in the west and has even attracted international musical collaborations such as Ya Habibi by Mohammed Ramadan (Egypt) and Gims (France). Multinational corporations like Orange™ and Vodafone use mahraganat artists in their branding. Mahraganat goes international: Ya Habibi by Mohamed Ramadan (Egypt) and Gims (France) Mahraganat & sha3bi in commercial branding: Oka w Ortega & Ahmed Sheba Orange™ commercial Popular Mahraganat Artists Like any other genre of music, the music within mahraganat varies. Artists like Hassan Shakoosh and Omar Kamal (Bint el Giran and Lghbatita) perform a style of mahraganat that is lighter in feeling and content.

Mohamed Ramadan, actor turned singer, used to predominantly perform mahraganat (Mafia) but has started to move into rap (Enta Gad3).

One artist who has made incredible moves on the Egyptian music scene, Wegz (Dorak Gai), performs trap (a type of hip hop that originated in the Southern US during the early ‘90s) not mahraganat. However, Wegz recently teamed up with Hassan Shakoosh to create Salka, mostly mahraganat with a trap flair.

Some mahragan songs have more of a sha3bi feel, some are mahraganat through and through but are still dance-show performable (Mahragan Enty M3lma and Ekhwaty) while others are straight party songs (ElSheyaka Ayza Mnena Eh). Mahraganat Dance All this information is well and good, but this is a belly dance blog, so let's discuss mahraganat in terms of dance and dance performances. The dancing performed to mahraganat at street parties incorporates hip hop and break dance movements with the raqs baladi with which we are all familiar. It is often incredibly athletic (sometimes ridiculously so) can be aggressive, and usually features matwah and machetes. Mahragan dancing at a Cairo street party Belly Dancing & Mahraganat This isn’t to say that you can’t or shouldn’t perform to mahraganat. It’s a fun music meant for dancing. And because this music is so popular in Egypt, it is expected for working dancers in the Egyptian entertainment scene to perform it in their sets. However, mahraganat music does not generally serve raqs sharqi movement since it's so different from raqs sharqi music. When performing it as part of their set, belly dancers may incorporate a mix of raqs baladi movements, hip hop, matwah dancing gestures and gestures and expressions that reflect the meaning of the lyrics. Like with raqs sharqi, raqs baladi, or traditional folk dance, each dancer has their own style so roll with it, study your music, make sure it is appropriate for your audience and create your own mahraganat performance style! Star belly dancer Dina performing mahragan Arab-Brazilian belly dancer Najla Ferreira performing in Cairo to Bint el Giran Other Dancers' Take On Mahraganat Other belly dancers have recently shared their own information about mahraganat. See their take below: Amaria Selene (USA/Egypt) - About Mahraganat Shahrzad (USA/Egypt) - WTF IS MAHRAGAN?! WHY ARE PEOPLE BELLY DANCING TO IT?! About Our Guest Author Aasiyah is a lifelong dancer and raqs sharqi instructor who specializes in modern Egyptian technique. Known for fusing masculine and feminine elements in her dance, Aasiyah's authentic style has been developed from years of dedicated study of Egyptian dance, culture, and language. You can visit this page to learn from Aasiyah. Was This Post Helpful?Did you learn something from this post? Would you like to see more posts about mahraganat? Hit "like" below and leave a comment with your feedback!

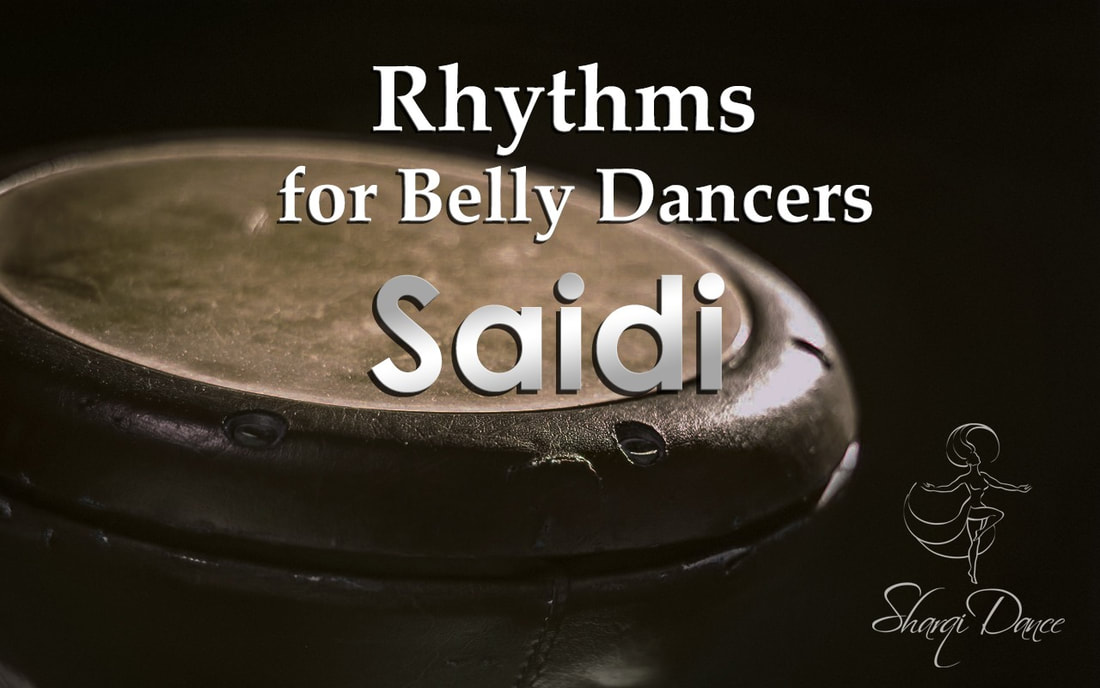

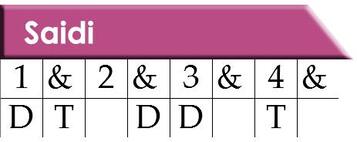

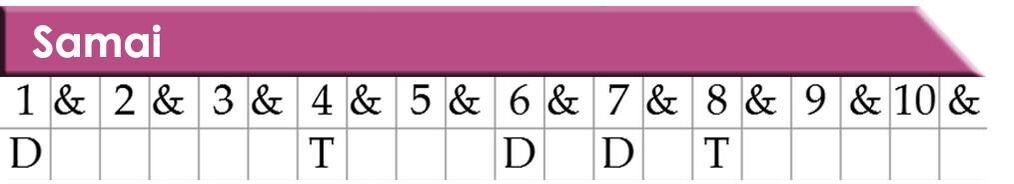

If you liked this article, you can visit our blog map to find other posts about Arabic music, belly dance and other related topics. Or subscribe to our newsletter to be the first to see more content from us! Happy learning, and happy dancing! Learn to identify Saidi rhythm within and outside of Saidi music Saidi is one of the most popular 4/4 rhythms in belly dance music. The "skeleton" of the Saidi rhythm normally has a down beat ("doum" sound) on the 1, and two down beats in the middle (one falling between 2 and 3, and one on the 3): There are some variations of this rhythm that start with an up beat or silence instead of the down beat ("doum"), and there are also variations where there are 3 or even 4 "doums" in the middle! To avoid confusion, let's just stick with this more common variation of the Saidi rhythm for this post, and we can come back to other variations in later posts. Hear this version of the Saidi rhythm as the base rhythm in a drum solo: The word Saidi (صعيدى, sometimes spelled Sa'idi) means from Upper Egypt. The Said, (Upper Egypt) is a region in the south of Egypt. It's called Upper Egypt because it has a higher elevation than the north of Egypt (Lower Egypt), which is closer to sea level. Fun fact: the Nile river flows to the north for that reason! Basically, anything that comes from Upper Egypt could be referred to as Saidi: clothing, food, music, dances, people... anything! In the context of belly dance or Middle Eastern music, when we talk about Saidi we are usually either referring to the music or dances from the Saidi region, or to the Saidi rhythm. Saidi Rhythm =/= Saidi Music? The name of this rhythm seems to indicate it's a rhythm from Upper Egypt, and it is an extremely common rhythm in Saidi music, but it's important to know that this rhythm is not exclusive to the Saidi region! Saidi rhythm is actually super common in Middle Eastern music across genres, including classical, baladi, shaabi, pop, drum solos, and folkloric. And you will find it across the borders of the Arab world, even in music from Lebanon and Syria for example. So while it might be tempting to assume that you are listening to Saidi music when you hear the Saidi rhythm, that isn't always the case. We also can't assume Saidi music will only feature this rhythm we call Saidi, although it primarily does. When you hear Saidi music you might also encounter other rhythms such as baladi, maqsum, malfuf, or fellahi. Here's an example of a famous Saidi song which does feature Saidi rhythm: Baladna (as played by Upper Egypt Ensemble) Here's an example of Saidi rhythm in a composition that is not Saidi: Warda (from 1:11 until 1:49) Here's another example of a Saidi song with Saidi rhythm, this time with dancing! Vanessa of Cairo dances to Sallam Allay There is so much left to be said about Saidi music and dance, so for now I will leave you with these examples. Pay attention to the rhythm in these examples, try to count it out, sing out the "doums" and the "teks" to help you identify the down beats and the up beats in this rhythm. In our next post we will discuss Saidi music and dance, and how you can learn to dance to Saidi rhythm in the specific context of Saidi music. Was This Post Helpful?Was this post helpful? Would you like to learn more about Middle Eastern music and dance? Hit "like" below and leave a comment with your feedback! You can also visit our blog map to find more posts like this, or subscribe to our newsletter, YouTube channel, or Facebook page to be the first to find out about our next post. Happy learning, and happy dancing! Learn to identify, dance to, and appreciate the beautiful but strangely-timed rhythm Sama'i The Samai rhythm is a 10/8 rhythm that is fairly common in certain types of Middle Eastern music. The 10/8 variation of this rhythm is referred to in Arabic as Samai Thaqil (also spelled Sama'i Thaqil), and that's the variation we are discussing today. The rhythm Samai is not featured in most Middle Eastern songs we normally use for belly dance, but it is encountered often enough to be considered an essential rhythm for belly dancers to know. The "skeleton" of the 10/8 Samai sounds like this: D--T-DDT-- This is spread over a count of 10, meaning there are 10 beats to each measure. Here's where the main "doums" and "teks" will fall within the Samai rhythm: Depending on the drummer and context, you might hear some or all of the silent spaces between the main doums and teks get filled out with more "teks" and "kas," drum rolls and other flourishes, but the timing and the skeleton of the rhythm stays the same. Listen to the Sama'i Thaqil Where You Might Hear Samai Most commonly, you will hear Samai in muwashah music, which is a type of Arabic poetry in musical form that dates back to 10th century Moorish Spain (Al-Andalus). Among belly dancers, the most famous muwashah is Lamma Bada Yatathana. There are many versions of this song available today, but it dates all the way back to Andalusia in the Middle Ages, and was first recorded in 1910. My favorite 20th century rendition of Lamma Bada: Samai: Not Just for Muwashahat You will sometimes hear the Samai rhythm as a section within a Middle Eastern musical composition, usually in the following genres:

The sama'i rhythm starts at 2:55 How Do We Dance to That? How you should dance to this rhythm will depend on the context such as the music it's found in, what the accompanying instruments are doing, and of course, your own personal preference and interpretation. For example, in muwashahat or in a more classical piece, the music might call for traveling steps such as arabesques and sweeping, ballet-like arm movements and leg lines. The energy is calm, soft, flowy and regal. Hip movements would be subtle and used sparingly, if at all. Watch Haleh Adhami's gorgeous interpretation of Sama'i in muwashah style In a drum solo, you can opt for the same types of movements and feeling as well, but if the solo tabla is dominating the base rhythm with a lot of accents, drum rolls and flourishes, you may opt to interpret those instead, and in that case fast, sharp hip movements could be appropriate. So context is definitely important! Was this post helpful? Would you like to learn more about Middle Eastern music and dance? Hit "like" below and leave a comment with your feedback! You can also visit our blog map to find more posts like this, or subscribe to our newsletter, YouTube channel, or Facebook page to be the first to find out about our next post. Happy learning, and happy dancing! You can learn how to dance to this and other Middle Eastern rhythms in my Belly Dance Rhythms & Combos online class, or learn how to play them in April's Darbuka Classes online.

2020 has been a real roller coaster. I think most of us have been through the whole gamut of emotions this year--sometimes even within a single day. We're facing a pandemic with risks to our health and life, extreme economic uncertainty, political chaos and division, social isolation, grief and loss just to name a few. Never in our lives have we had so little control over our outside circumstances. Which means it's never been more important to turn inward and focus on the things we can control. We can't stop the storm from raging all around us, but we can root ourselves down into the "soil" of our inner being to seek nourishment and strength so that we can withstand it. We can remain adaptable and flexible so that fierce winds can bend us but never break us. We can mourn the loss of a few branches while being grateful that after the storm has passed on, we can still stand tall. When we're feeling carried away by the winds and the rain and the thunder, when we are overwhelmed by fear, anxiety, sadness or stress, we can use breath and movement to ground ourselves and shift our emotions naturally from within. Sometimes it takes no more than a quick and simple regular movement practice to divert our negative feelings and trick our bodies into feeling better. When we are rooted and grounded from within, we feel calm and become much better able to withstand any storm. -Yamê Stress Relief Workshop

Alf Layla wa Layla is one of the most well-known songs by Um Kultum, and one of the most famous belly dance songs of all time. Do you know what it means? The song Alf Layla wa Layla is ubiquitous both in the belly dance community and in the Arab world. Originally sung by Um Kulthum, this immortal classic has crossed language barriers and won the hearts of people all over the world. It is considered by some to be one of the best recordings ever made in music history. Since you've clicked on this article I assume you're already familiar with this song, so let's dig a little deeper into its background and meaning. Composer, Lyricist & Singer Alf Layla wa Layla (also spelled Alf Leilah wa Leilah, Alf Leila wa Leila, Alf Leyla wa Leyla, Alf Lela Wlela, among other variations) was composed in 1969 by Baligh Hamdi, a prominent Egyptian composer in the 1960's and 70's, written by Egyptian poet Morsi Jamil Aziz and sung by the legendary singer Um Kultum. Um Kulthum (1904? - 1975) Born "Fatima Ibrahim as-Sayed El-Beltagi" in Egypt, Um Kulthum was a poor girl from a rural town who grew up to become the most well-known Arab singer of her time, which she remains so to this date, even 45 years after her death. Due to her incredible vocal ability, style and fame she was given the title of "Star of the East." Her funeral in 1975 was attended by over 4 million Egyptians, and her music is still heard and recognized by Arabs all over the Middle East and around the world. Many of the most popular belly dance songs we hear today were originally sung by her. A Thousand and One Nights Alf Layla wa Layla means 1001 Nights, and it is one of Um Kulthum's most enduring songs. Here is a small piece of it translated, so you can understand its meaning: Oh beloved The night and the sky, and its stars and its moon Its moon and its night-time liveliness, and you and I Oh beloved, oh my life All of us, all of us experience love equally And love, how heart-aching it can be Love, how heart-aching it can be Love stays up with us to shower us with bliss And it says serenely to us Oh beloved, come let us dwell in the eyes of the night Come let us dwell in the eyes of the night And we'd say to the sun: come out, come out But only after a year from now And not before a year has passed For this is a beautiful night of love Worth a thousand and one nights more For what is a lifetime but a sole night just like tonight, just like tonight Tonight, just like tonight If you'd like a more complete translation, I highly recommend the 100 Songs Initiative video translation below, which includes the original words in Arabic as they are spoken, along with the transliteration and translation in English. Favorite Recordings The original recordings of Um Kulthum's music are typically 30-80 minutes long and are not meant to be danced to. However, they are still wonderful for us as belly dancers to listen to so that we can gain more appreciation and understanding for the music. For dance performances, we typically use much shorter and more modern renditions of the original classic compositions, and they can be purely instrumental or feature a vocalist. You can listen to a few of my favorite recordings of Alf Layla wa Layla below. Full Length Alf Layla wa Layla Sung by Om Kulthum Instrumental Version, Alf Layla va Laylah by Samir Instrumental Version, Alf Leyla Wa Leyla by Aziza Alf Leyla We Leyla as Sung by Sherine Do you love Alf Layla wa Layla? What version is your favorite? Share your thoughts in the comments below! Was This Post Helpful?If you liked this article, you can visit our blog map to find other posts about Middle Eastern music and dance and other related topics. Or subscribe to our newsletter, YouTube channel, Facebook and Instagram pages to be the first to see more content from us!

Happy learning, and happy dancing! |

AuthorYamê is a Brazilian-American View Posts By CategoryIf you'd like to read more articles by Yamê or SharqiDance's guest authors, please view our blog map here.

Archives

January 2024

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed